Couscous has for centuries been the principle staple of the Maghrebi cuisine, from the North African region of Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia. Made from semolina, the hardest part of the durum wheat kernel, couscous originated from the ethnic community of Berbers, indigenous to the region around the 12th century. Meaning ‘well rolled’ from their ancient language, making couscous from scratch is a culinary pastime passed down through the generations of Maghrebi matriarchs and still practised in Sephardi communities.

For generations, the Tunisian Jewish community made couscous every Tuesday and Friday when bakeries were closed. It became the tradition for families to eat couscous instead of bread, served with a simple vegetable soup midweek, and a more substantial dish called ‘boulet’ for the Shabbat dinner. Couscous became known as ‘poor man’s food’, as it was cheap to make, hearty and filling and fed the whole family.

I was inspired to write about the culinary culture of making couscous from scratch by two sisters with Tunisian heritage, Ruti and Ronit and Yael, Ruti’s daughter in law. On Tuesday morning, armed with steamers, sieves and kilos of semolina flour, we embarked on making their mother’s traditional recipe of boulet for hundreds of hungry soldiers. It started with the couscous. Making these fluffy, tasty grains from scratch is a labour of love, as it involves steaming the grains twice and sieving the semolina by hand in a process that takes around 3 hours. There is also the vegetables that need preparing for the soup and a citrus sour, seasonal salad that always accompanies the finished dish.

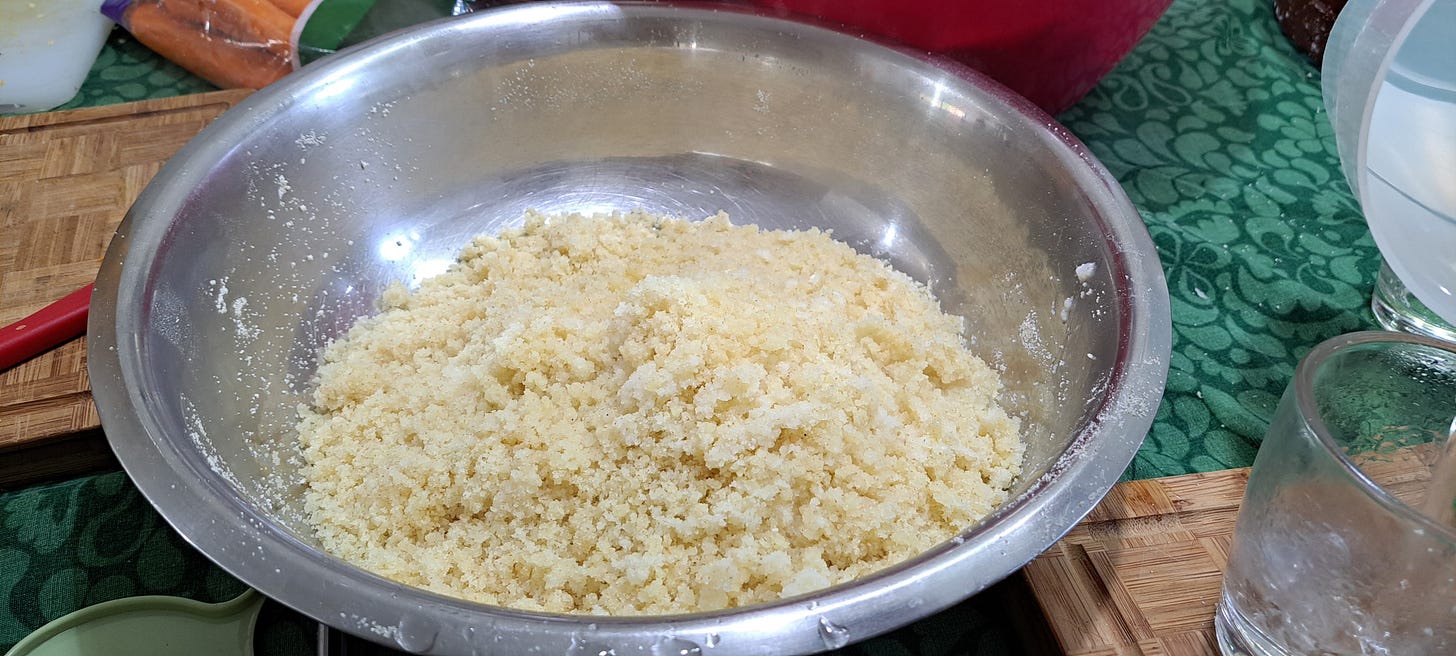

7 kilos of semolina flour sat proudly in the kitchen, each kilo bag costing 5 NIS, approximately 0.95p. First off, pans of water were put on the hob to boil with a steamer and lid on top of each one. Each kilo of semolina flour was poured into a large metal bowl and a cup of water was slowly added and mixed together by hand to form clumps, resembling coarse breadcrumbs. This was then emptied into the large holed ‘couscous’ sieve where every grain of semolina was hand rubbed through into the awaiting bowl. One and a half tablespoons of coarsely ground sea salt was then added and mixed in with one cup of vegetable oil. After one final stir, the couscous was piled into the steamer, and placed on top of the pan in a rolling boil, covered with tight fitting lid and a towel, before being left to steam for exactly 55 minutes.

Once the cooking time was up, the steamer was removed from the pan and the grains put back into the large metal bowl. The saucepan was topped up with boiling water ready for the second steam. Two cups of water was then mixed into the cooked semolina to swell the grains. Clumps were thinned out by hand and the couscous well aerated, before returning to the steamer for a further 25 minutes. The couscous was then removed from the steamer, placed back in the metal bowl and one more cup of water added together with one final stir before the grains were left to cool with a towel covering the bowl. We were soon to be rewarded with soft, fluffy and a very delicious couscous.

Whilst the couscous was cooking, we moved onto the vegetable soup and salad. The authenticity of this dish relies on a variety of root vegetables and North African spices that gives its distinctive flavour. Potatoes, carrots, onions pumpkin, courgettes and fennel are peeled and roughly chopped into large chunks and placed in a large pan with plenty of salt together with a blend of turmeric, paprika, cumin and black pepper, often referred to as the ‘couscous spice’. Completely immersed in water, the soup is place on a medium heat for 2 hours to cook and develop the much loved flavours of this rustic, homely, warming dish. Boulet would not be complete without the accompanying salad of thinly sliced carrots, peppers and kohlrabi, soured by a dressing of freshly squeezed lemon juice.

The making of couscous from scratch is lovingly considered to be ‘women’s work’. It is inherent to the Maghrebi Jewish community, affording so much pleasure to the matriarch when all her family, from the youngest to the eldest gather around her table and she delights in feeding each mouth with the freshly prepared couscous covered with hot chunks of vegetables and a flavoursome broth.

This is a nourishing dish made with lots of love and plenty of flavour, while epitomising the Jewish tradition of feeding, an act of human kindness. Sustaining the our troops in the field remains our daily work in The Kitchen Garden. Each day we continue to prepare, cook and send hot, tasty food to 400-500 hungry soldiers of different culinary backgrounds and all with different palates. We mix up the menu with Ashkenazi, Sephardi and Mizrachi dishes, to give them a taste of home cooking incorporating heat, spice, sour and umami flavours. Couscous, vegetables, soup, salad and a side potion of roasted chicken was made for them this week as a labour of love and a small token of thanks and appreciation, in these crazy and challenging times.